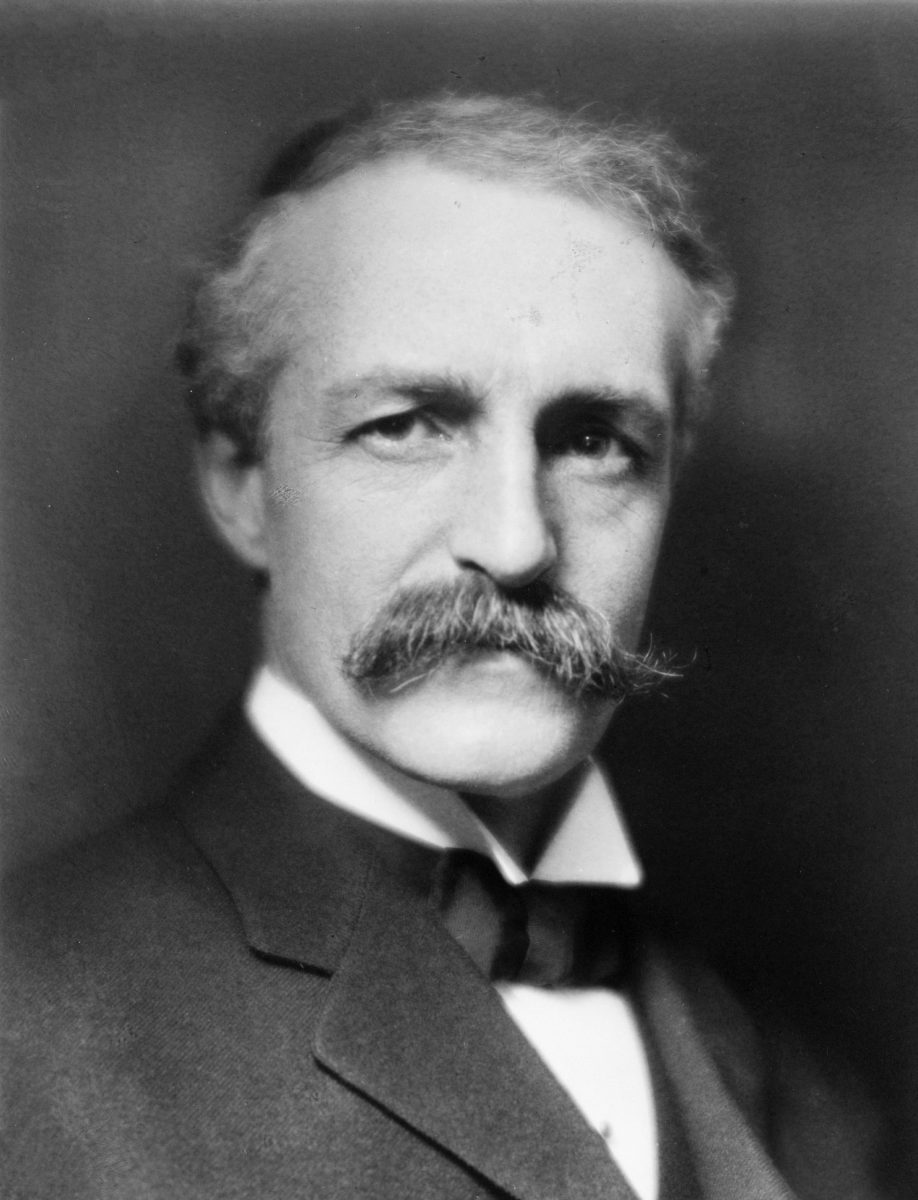

President Theodore Roosevelt, a good friend of Pinchot’s, said “… Among the many, many public officials who under my administration rendered literally invaluable service to the people of the United States, Gifford Pinchot on the whole, stood first.”

The following is an excerpt from Pinchot’s book The Fight for Conservation, from the chapter entitled “The Moral Issue.”

The central thing for which Conservation stands is to make this country the best possible place to live in, both for us and for our descendants. It stands against the waste of the natural resources which cannot be renewed, such as coal and iron; it stands for the perpetuation of the resources which can be renewed, such as the food-producing soils and the forests; and most of all it stands for an equal opportunity for every American citizen to get his fair share of benefit from these resources, both now and hereafter.

“[Conservation] recognizes equally our obligation so to use what we need that our descendants shall not be deprived of what they need.”

Conservation stands for the same kind of practical common-sense management of this country by the people that every business man stands for in the handling of his own business. It believes in prudence and foresight instead of reckless blindness; it holds that resources now public property should not become the basis for oppressive private monopoly; and it demands the complete and orderly development of all our resources for the benefit of all the people, instead of the partial exploitation of them for the benefit of a few. It recognizes fully the right of the present generation to use what it needs and all it needs of the natural resources now available, but it recognizes equally our obligation so to use what we need that our descendants shall not be deprived of what they need.

Conservation has much to do with the welfare of the average man of to-day. It proposes to secure a continuous and abundant supply of the necessaries of life, which means a reasonable cost of living and business stability. It advocates fairness in the distribution of the benefits which flow from the natural resources. It will matter very little to the average citizen, when scarcity comes and prices rise, whether he can not get what he needs because there is none left or because he can not afford to pay for it. In both cases the essential fact is that he can not get what he needs. Conservation holds that it is about as important to see that the people in general get the benefit of our natural resources as to see that there shall be natural resources left.

“Conservation is the application of common-sense to the common problems for the common good.”

Conservation is the most democratic movement this country has known for a generation. It holds that the people have not only the right, but the duty to control the use of the natural resources, which are the great sources of prosperity. And it regards the absorption of these resources by the special interests, unless their operations are under effective public control, as a moral wrong. Conservation is the application of common-sense to the common problems for the common good, and I believe it stands nearer to the desires, aspirations, and purposes of the average man than any other policy now before the American people.

The danger to the Conservation policies is that the privileges of the few may continue to obstruct the rights of the many, especially in the matter of water power and coal. Congress must decide immediately whether the great coal fields still in public ownership shall remain so, in order that their use may be controlled with due regard to the interest of the consumer, or whether they shall pass into private ownership and be controlled in the monopolistic interest of a few.