Leaving civilization behind is the goal of many of us hikers, hunters and outdoor enthusiasts. It is easy to forget, however, that stepping into the wilderness and out of the madness is a privilege essentially unique to the United States and Canada.

Yet this entitlement is not something that was simply switched on but rather was developed over time — largely in response to the depletion of our natural resources — and ultimately came to be defined as the North American Model of Conservation.

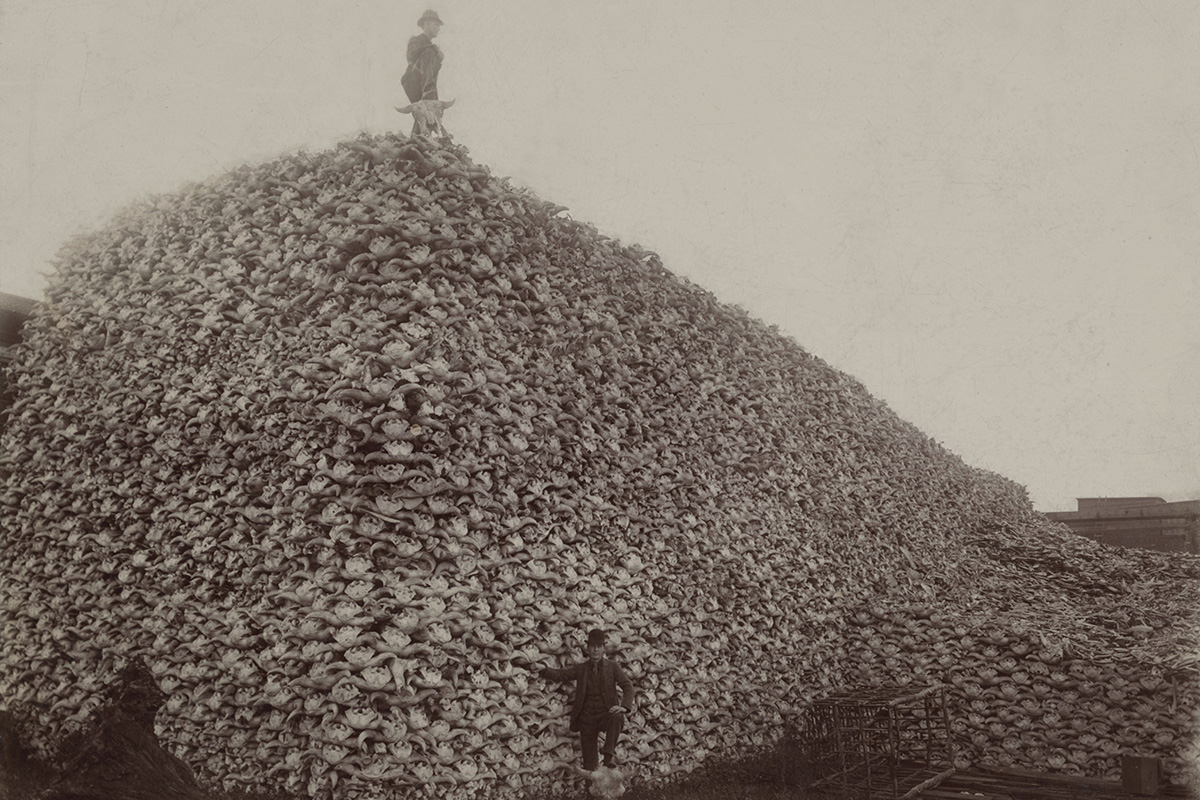

In 1874, for example, in the span of one month, Michigan hunters killed approximately 25,000 passenger pigeons per day, according to the The Audubon Society Encyclopedia of North American Birds. Also, according to the Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife, the population of American Bison declined from 40 million in 1830 to an estimated 300 in 1900. That same year, it is estimated that the whitetail deer population, which currently hovers around 30 million, had bottomed out at its all time low of 500,000.

Wildlife in the United States was under siege.

It was decided that wildlife would be owned by the people — a reaction to and rejection of the idea that only the wealthy aristocracy were allowed to hunt.

To make matters worse, trains moving entrepreneur-hunters further into the frontier, returning with their harvest encased in ice to the big city, made satiating the masses of their newly acquired taste for wild game a big industry. One that was soon booming at a rate that was impossible to sustain.

When the first European settlers landed in the New World, the bitter taste of an oppressive monarchy still lingering, they chose to take a different approach to wildlife than that of their home nation. While wild animals in England were owned by the King, in this new land, it was decided that wildlife would be owned by the people — a reaction to and rejection of the idea that only the wealthy aristocracy were allowed to hunt.

That idea — that wildlife belonged to all citizens — became a basic principle of the North American Model of Conservation.

This basic principle was expanded upon and cemented by law in 1896 as a result of the court case Geer v. Connecticut. Thereafter, management and conservation of wildlife became the responsibility of the individual states. Soon, many other laws focused on conservation began to gain traction.

As these laws were cutting the trail, hunters began marching it. In reaction to the devastation of certain animal populations and the belief that hunting should be available for all, the conservation minded launched a movement.

Theodore Roosevelt, George Bird Grinnell, and Gifford Pinchot fought for the creation of regulations aimed at and formed conservation groups focused on protecting wildlife and public lands from exploitation. Many of these regulations became essential components of what was eventually, in 2001, described by biologists Valerius Geist and Shane P. Mahoney as the North American Model of Conservation.

The seven pillars — also referred to as “sisters” — comprising the model are presented as follows by Mahoney:

Wildlife resources are a public trust. Challenges include (1) inappropriate claims of ownership of wildlife; (2) unregulated commercial sale of live wildlife; (3) prohibitions or unreasonable restrictions on access to and use of wildlife; and (4) a value system endorsing an animal-rights doctrine and consequently antithetical to the premise of public ownership of wildlife.

Markets for game are eliminated. Commercial trade exists for reptiles, amphibians, and fish. In addition, some game species are actively traded. A robust market for access to wildlife occurring across the country exists in the form of leases, reserved permits, and shooting preserves.

Allocation of wildlife is by law. Application and enforcement of laws to all taxa are inconsistent. Although state authority over the allocation of the take of resident game species is well defined, county, local, or housing-development ordinances may effectively supersede state authority. Decisions on land use, even on public lands, indirectly impact allocation of wildlife due to land use changes associated with land development.

Wildlife can be killed only for a legitimate purpose. Take of certain species of mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians does not correspond to traditionally accepted notions of legitimate use.

Wildlife is considered an international resource. Many positive agreements and cooperative efforts have been established among the U.S., Canada, Mexico, and other nations for conserving wildlife. Many more species need consideration. Restrictive permitting procedures, although designed to protect wildlife resources, inhibit trans-border collaborations. Construction of a wall to prevent illegal immigration from Mexico to the U.S. will have negative effects on trans-border wildlife movements and interactions.

Science is the proper tool to discharge wildlife policy. Wildlife management appears to be increasingly politicized. The rapid turnover rate of state agency directors, the makeup of boards and commissions, the organizational structure of some agencies, and examples of politics meddling in science have challenged the science foundation.

Democracy of hunting is standard. Reduction in, and access to, huntable lands compromise the principle of egalitarianism in hunting opportunity. Restrictive firearms legislation can act as a barrier hindering participation. To help address these challenges, this review presents several recommendations. These are offered as actions deemed necessary to ensure relevancy of the Model in the future.

In comparison to other models of conservation around the world, the North American Model rises to the top.

While these pillars describe the rule of law, they also provide an excellent rubric for successful conservation techniques. A study conducted by the University of Maryland in partnership with the Heinz Center for Science, Economics, and Environment concluded that in comparison to other models of conservation around the world, the North American Model rises to the top. The two models to which North America’s was compared are those of South Africa, where wildlife is under private ownership, and the No-Hunting Model, in which wildlife is owned by the government. The key differences between these three is the lawful ownership of wildlife and the sources of funding for conservation.

The study describes a key benefit of the North American Model as being “a dedicated federal funding mechanism [which] ensures that a majority of wildlife management costs are covered by excise taxes, paid by hunters and anglers.”

The South African Model generates funding through both tourism and hunting, and “empower[s] individuals and local communities with ownership and/or rights over the management of wildlife, enabling them to benefit from the existing opportunities in the tourism industry.” This model has shown some success but is wrought by human and animal conflict, as well as heavy poaching.

The No-Hunting Model, for which the study uses India as an example, derives funding for conservation through tourism alone. On average, this only covers approximately half of all such costs, forcing the government to subsidize the remainder.

In both of the alternative models, the study shows more large mammal species in decline.

The study’s authors seem to suggest that there is room for outdoor enthusiasts to aid conservation efforts by more directly contributing funds.

The North American Model, however, is not perfect. Threats to this system include the “privatization of wildlife and land” and the fact that “non-consumptive users don’t directly pay for conservation the same way that consumptive users do.” By this, the study’s authors seem to suggest that there is room for outdoor enthusiasts — those who do not engage in hunting — to aid conservation efforts by more directly contributing funds.

Although our model is not infallible, Americans and Canadians should be proud of their efforts to conserve North America’s natural resources.

In the words of Mahoney, “The model itself is not a monolith carved in stone; it is a means for us to understand, evaluate, and celebrate how conservation has been achieved in the U.S. and Canada and to assess whether we are prepared to address challenges that lay ahead.”